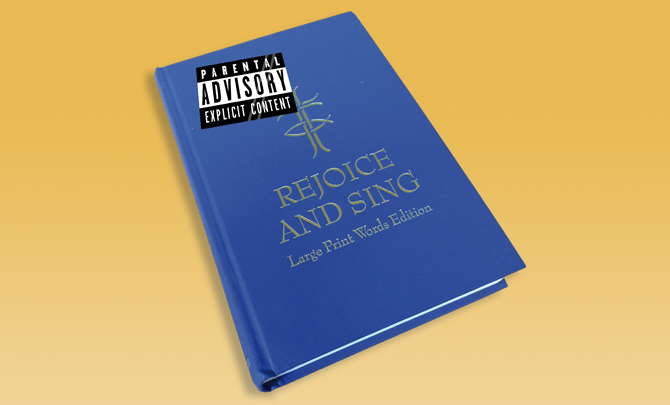

Jumble sales of the apocalypse: Rude hymns - Reform Magazine

Simon Jenkins on rude hymns

In the words of the continuity announcements on Channel 4, this column may contain strong language and scenes of a sexual nature from the start. Our subject this month is sex and hymns. You might not think sex has much to do with hymns, but just like Samson and Delilah, the two of them have a surprising amount of intercourse.

And therein lies the first problem with many hymns written in Victorian and earlier times: old-fashioned English is the double entendre’s friend. Most churches know this, and have wisely stopped talking about Sexuagesima Sunday if only because it is used to triple the number of excitable people cramming into church.

I’ve always found singing in church a joy, but some hymns make you smile for all the wrong reasons. For a start, they use words that lead very different lives in other parts of your brain. Words such as bare, bondage, bosom, bowels, breast, bush, desires, conquest, flesh, gay, kiss, loins, lover, organ, prostrate, queen, rude, seed, submission, succour, tossed, virgin, womb – and not forgetting good old intercourse. Or, as the hymn writer William Bathurst put it: ‘Let our hearts, from sin made free,/ Hold sweet intercourse with thee.’ Try reading those lines out with a steady voice as you announce the hymn. I’m sure my first ever encounter with most words from the lexicon of love happened while I was singing in Sunday school, which must make the hymn book a crash course in sex education.

One candidate for ‘Hymns Ancient and Freudian’ is the old standard ‘Fill Thou my Life, O Lord my God’, with the awkward lines: ‘Praise in the common things of life,/ Its goings out and in’, which have been known to make people spray Baptist Communion cordial over the pew in front. It doesn’t help that the man who wrote these words rejoiced in the name of Horatius Bonar. Another example is the Book of Common Prayer’s Alleluia verse for the 20th Sunday after Trinity. A former chorister who sang the words, said: ‘I was expected to respond to the versicle with: “I will sing and give praise with the best member that I have.”’

These days, vicars and ministers wisely omit the offending verses from suggestive hymns, but sometimes the wrong verse is taken out. This happened to me recently when we were singing ‘All Things Bright and Beautiful’. We sensibly omitted the verse about how we gather rushes by the water every day, but unaccountably left in the verse concerning ‘the purple headed mountain’. On the same subject, I remember leaving church one Sunday after we’d sung ‘Come, thou fount of every blessing’, with its stirring line: ‘Here I raise my Ebenezer’. At the church door, a perplexed friend of mine asked the minister: ‘How exactly does one raise one’s Ebenezer?’ He was advised to see his doctor.

Some hymns are so littered with innuendo they must test the humour reflexes of the stuffiest saint. Take the lovely, lively hymn ‘Thou Didst Leave Thy Throne and Thy Kingly Crown’; all goes well until: ‘But thy couch was the sod, O thou Son of God’. The same goes for the serene and sleepy children’s hymn, ‘Now the Day is Over’, which waits until verse four before delivering this heartfelt prayer:

Grant to little children

Visions bright of Thee;

Guard the sailors tossing

On the deep blue sea.

Even the most treasured songs aren’t immune from sacred smut. Try keying into Google the bold declaration: ‘We like sheep.’ You’d think the search results would show the top 10 jokes about the dating habits of Welsh shepherds, but instead we get the famous duet chorus from Handel’s Messiah, which has been known to reduce school-age choristers to tears of laughter.

Hymnbook publishers over the past 50 years have been quietly dropping anthems which are just too eccentric now. Their cull has deprived us of hymns such as ‘The Happy Eunuch’, ‘The Earth Is Gay’, ‘What Was it Made my Bosom Swell?’ and a splendid 18th-century specimen: ‘Blest is the Man whose Bowels Move’. Even the Victorians realised this line was open to a second meaning, so they edited it to: ‘Blest is the man whose breast can move’, which was so much better. Personally, I think the hymn censors should leave well alone. Our hymns are fabulous just as they are – bosoms, Ebenezers and all.

Simon Jenkins is editor of shipoffools.com. Follow Simon on Twitter: @simonjenks

___

This article was published in the October 2016 edition of Reform.

Submit a Comment